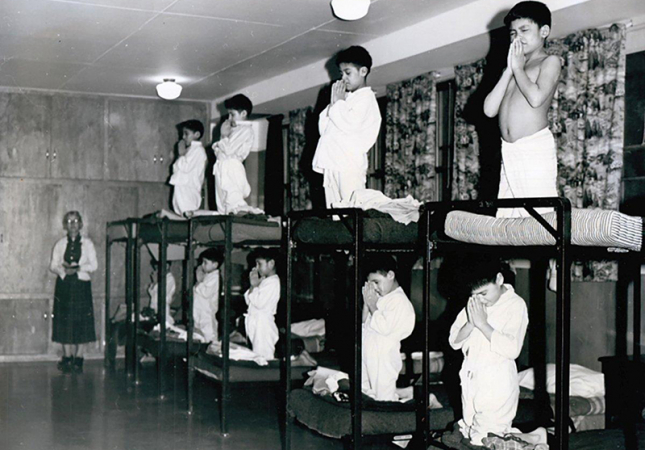

Indigenous boys pray on bunk beds in a dormitory at the Bishop Horden Memorial School, a residential school in the indigenous Cree community of Moose Factory, Ontario, in 1950. Recent confirmation of hundreds of unmarked graves on the grounds of two former residential schools for Indigenous children in Canada has prompted a U.S. Department of the Interior inquiry into U.S. boarding schools for Native Americans, which were often run by churches. (CNS photo/Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre, Handout via Reuters)

By: Carol Zimmermann

WASHINGTON (CNS) — In response to a late June announcement, the United States will be conducting an investigation of former federally funded boarding schools to search for graves of Native American children, a spokesperson for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops said June 28 the bishops will “look for ways to be of assistance.”

“It is important to understand what might have occurred here in the United States,” said the statement from Chieko Noguchi, who added the bishops will be “following closely” the investigation announced June 22 by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland.

Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico and is Catholic, announced this upcoming review, called the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, during her remarks at the virtual conference of the National Congress of American Indians.

“I know that this process will be long and difficult. I know that this process will be painful. It won’t undo the heartbreak and loss we feel. But only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud to embrace,” she said.

Many of these government-funded schools were church-run boarding schools.

The U.S. Interior Department’s initiative was prompted by the recent discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. Just two days after the U.S. initiative was announced, 751 unmarked graves were discovered at a second site, a former Catholic residential school in Saskatchewan.

“We are deeply saddened by the information coming out of two former residential boarding school sites in Canada. We cannot even begin to imagine the deep sorrow these discoveries are causing in Native communities across North America,” said Noguchi in her statement.

By “bringing this painful story to light,” she added, “may it bring some measure of peace to the victims and a heightened awareness so that this disturbing history is never repeated.”

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition said in a June 25 statement that it felt “deep gratitude” for the upcoming investigation, which it said will “provide critical resources to address the ongoing historical trauma of Indian boarding schools. Our organization has been pursuing truth, justice and healing for boarding school survivors, descendants and tribal communities.”

The group, based in Minneapolis, has identified 367 “historically assimilative Indian boarding schools that operated in the U.S. between approximately 1870 until 1970,” but it has only been able to locate records from 38% of these schools.

“Because the records have never been fully examined, it is still unknown how many Native American children attended, died or went missing from Indian boarding schools,” the statement said. “We believe that the time is now for truth and healing. We have a right to know what happened to the children who never returned home from Indian boarding schools.”

On its website, the coalition points out that over 350 government-funded, and often church-run, boarding schools operated across the country in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Although the group said it does not have an accurate count of the number of children who were placed in these schools, it said it was likely hundreds of thousands.

It also notes that these children were voluntarily or forcibly removed from their homes and families and “punished for speaking their Native language, banned from acting in any way that might be seen to represent traditional or cultural practices, stripped of traditional clothing, hair and personal belongings and behaviors reflective of their Native culture.”

These school in the U.S. came about after the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, which aimed to introduce “habits and arts of civilization” to Indian tribes.

The new initiative, which will present a final report next April, will not only identify the locations of these former residential schools in the U.S. but also will identify where there may have been burials and what tribes the attending students were from.

In Canada, not only have hundreds of graves been detected at two former residential schools, but an investigation by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the past six years has revealed accounts of brutality, neglect and sexual abuse within the network of these schools.

Chief Cadmus Delorme of Canada’s Cowessess First Nation has called for a papal apology for what has happened, saying it would be “one stage of many in the healing journey.”

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops announced June 10 that a delegation of “elders/knowledge keepers, residential school survivors and youth from across the country” representing First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities is preparing to travel to the Vatican.

Archbishop Donald Bolen of Regina, Saskatchewan, said Pope Francis would be able to listen to their stories and hear, in person, what they need from him and the church.

In Vancouver, British Columbia, Archbishop J. Michael Miller has said the archdiocese will “offer to assist with technological and professional support” to help the affected nations in whatever way they choose to honor, retrieve and remember their deceased children.”