When Father Michael Steltenkamp, S.J., arrived at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota as a young man, he never could have imagined that God would lead him to being a primary consultant for the cause of canonization of the man who sparked his interest in Native American culture and history: Nicholas Black Elk.

Father Mike’s path began when he read Black Elk Speaks by John Neihardt. Written in 1932, it spoke of the Lakota (Sioux) man’s spiritual visions, involvement in the Battle of Little Bighorn, experiences as a medicine man and other aspects of his early life.

At the Jesuit-run Red Cloud Indian High School, Father Mike dreamed of meeting a relative of Nicholas Black Elk— maybe even his son, Ben— and hearing stories that were not yet published. Perhaps he, too, would write a book.

Father Mike did meet Ben, who passed away shortly thereafter. The young Jesuit thought his chance of learning more about Black Elk from his family was gone. But, as Father Mike often says, “Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous”—such as when the school’s furnace broke down one day.

With his students dismissed, Father Mike went outside. There, sitting on a bench, was a woman named Lucy Looks Twice. He introduced himself to the elder, and that is how he met Black Elk’s only surviving child. They spoke for a while, and she said Father Mike was welcome to visit her.

Uncovering Nicholas Black Elk’s Catholic identity

The first time he visited Lucy, he brought a copy of Black Elk Speaks that he had filled with bookmarks, notes and questions. They spoke about her father’s experience in the prereservation era.

“To almost every question, she said, ‘No, he never talked about that,’” he said.

He began to wonder if she simply didn’t want to talk about sacred things, but he soon learned that wasn’t the case.

Finally, he asked Lucy what her father would want to share if he were to speak to his students at the high school.

“That’s when the floodgates opened. She said, ‘My father would like people to know about his work as a Catholic catechist,’” he said.

Father Mike describes the picture that previous books painted of Black Elk as “an old-time medicine man who pined for the old days, who was upset that so many changes had taken place and [that] the old-time religion had been abandoned.

”“Lucy fleshed out a different identity,” he said. Black Elk embraced Christianity in 1904 and was given the name Nicholas when he was baptized on Dec. 6, the feast of St. Nicholas. He spent 43 years as a catechist on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, merging his Lakota culture and Catholic faith. A Jesuit priest in the 1930s estimated that Black Elk was responsible for at least 400 baptisms on the reservation.

A scholarly interest and cause for canonization

Later pursuing a doctorate in anthropology at Michigan State University, Father Mike wrote his dissertation, titled No More Screech Owl: Plains Indian Adaptation as Profiled in the Life of Black Elk. It addressed how Black Elk lived out his faith as a catechist.

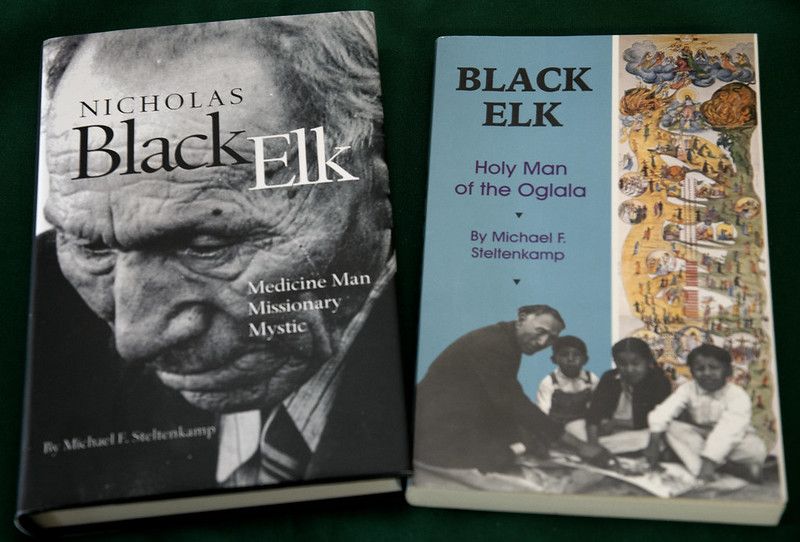

“The world never knew anything about his Christianity until Black Elk: Holy Man of the Oglala,” he said, referring to the biography he authored in 1993. He later wrote Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Missionary, Mystic (2009). After this publication, Black Elk’s impact on Father Mike’s life grew.

In October 2017, Nicholas Black Elk’s cause for canonization was opened by Bishop Robert Gruss while he was shepherding the Diocese of Rapid City, South Dakota. Nicholas Black Elk could become the first American Indian male to be canonized. (The first female Indian saint is Kateri Tekakwitha, canonized in 2012, while Juan Diego, canonized in 2002, is the first Mexican Indian saint.)

“It was Black Elk’s family who first approached Bishop Gruss of Rapid City to start the canonization process,” he said. “Then, on November 14— my birthday— Bishop Gruss ... introduced to the national Conference of Catholic Bishops the cause for Black Elk, and they unanimously accepted his name as somebody who should be investigated for canonization.” With this initiative affirmed by the USCCB, Nicholas Black Elk was declared a “Servant of God,” the first step in the process of sainthood.

Father Mike said he took the “coincidence” of this happening on his birthday as “God and Black Elk giving me a wink of the eye from heaven.”

At the request of Bishop Gruss, Father Mike provided input as to why he thought Nicholas Black Elk’s cause should proceed. After the cause was approved, he also provided clarifications for the cause’s postulator in Rome, Father Luis Escalante, who was further investigating the case. Now, Nicholas Black Elk’s grave is a pilgrimage site.

Bishop Gruss said one of Nicholas Black Elk’s talents was to “bring Lakota spirituality within the context of the Catholic faith and the sacramental life of the Church.”

“He could be both Lakota and Catholic at the same time,” Bishop Gruss said.

“Widely respected in secular circles, Nick (Black Elk) became a strong inspiration to Native peoples wondering if their embrace of Christianity was a sellout of their Indian tradition. Black Elk’s life showed them that to be a Christian Indian was to make a good decision,” Father Mike said. “They saw his commitment to the Gospel."

For that commitment to the Gospel, Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk is now considered a candidate for sainthood.

Father Michael Steltenkamp, S.J., currently serves as the parochial administrator of St. John XXIII Parish, which includes churches in Ryan, Merrill and Hemlock.

About Black Elk